The sun is beating down relentlessly as I guide Elaine, a walnut-bay horse with a dark mane, through the thorny acacia and dense shrub. It’s been a long day in the saddle, and my thighs are aching. Our camp is just across a ridge in the Lolldaiga Range of northern Kenya, a patchwork of diverse landscapes and communities.

Suddenly, Elaine’s ears flick back, alert, and her muscles tighten under me. Our guide, Nicholus Nangunye Tuta, stretches his arm toward a bush just a few meters away. I squint, trying to make out what the others have already seen: two amber eyes, glowing from the shadows. It’s a young lion, crouched low in the tall grass, quick and strong.

A tense silence hangs in the air.

Without the protective walls and high wheels of a safari vehicle, I feel completely exposed. Staring into the bush, I’m caught between awe and fear—the distance between myself and this apex predator seems almost laughably small. Usually, I’m the one tracking lions, camera in hand, but now, the lion shifts in my mind from a distant object to something much more present. I shift too, becoming acutely aware of my own vulnerability.

A dominant male lion rests at dusk, recently having faced competition from other nearby males. Nicholus gestures in the opposite direction, to a safer distance. He points to some tracks in the dust. “This is a big lion, and these are younger ones, probably cubs,” he says. “Most likely a mother.” The paw prints on the earth tell stories of more lions, heading in different directions. It’s time to move on.

Horseback safaris, which began in Kenya in the 1970s, remain the most immersive way to experience wildlife here. Riding a horse breaks down the barriers—designed to protect us but also to separate us from the natural world. In the thrill of the ride, we’re reminded of just how crucial it is to protect these wild places.

Out here, your horse becomes your translator, reacting to the subtle hiss of a leopard, the faint scent of a passing elephant herd, or the cool morning breeze sweeping down from Mount Kenya’s icy peaks. Your job is to learn how to listen.

Safari Tourism and Conservation

The next morning, we saddle up again and fall into a nose-to-tail line. The quiet of our conversation fades as we enter the light-dappled mountain forest. African olive trees spread their branches between towering cedar trees, and wild orchids hang from the branches. It’s a challenging path, but one that was made long ago by elephants grazing here. The trail winds like a river through the trees.

Just around a bend, the imposing form of Mount Kenya appears. Three million years ago, this singular volcano erupted from the Earth’s core, rising to 23,000 feet before the passage of time wore it down. Known as Kirinyaga by the Kikuyu people who considered it sacred, it’s now the tallest mountain in Kenya, after which the country is named.

Even though the glaciers have shrunk by 90% in the past 80 years due to global warming, ice still clings to the basalt peaks. The lush volcanic greenery of central Kenya gives way to the more sparse beauty of the arid plains and isolated mountains. The crops have given way to cows.

Like many conservancies in Kenya, Borana started as a cattle ranch, though this land has supported livestock for centuries. For generations, cattle were central to the culture and economy of the Maasai, Samburu, and Pokot people. When national parks and conservancies were created in the mid-20th century, these communities often found themselves cut off from grazing areas they had relied on for centuries.

Now, Borana is working to build stronger relationships with its neighboring communities, offering programs like Mazingira Yetu, which means “our environment” in Kiswahili. The program teaches environmental stewardship, allowing local students to visit the conservancy, go on game drives, meet the rangers, and learn about sustainable practices like water conservation, regenerative farming, and tree nurseries. Launched in 2022, the program brought 365 students to Borana. By 2023, the number had grown to over 1,100 students.

(Here are five alternative ways to enjoy a game drive, from cycling to camping.)

All profits from Borana are reinvested into conservation efforts. In 2023, tourism generated over $1 million, which supported the protection of 28 endangered species, the training of 114 rangers, scholarships for 55 students, and drought relief for seven communities. However, it’s becoming increasingly clear that long-term conservation requires cooperation across borders, communities, and interests.

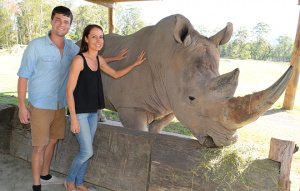

A mother northern white rhinoceros and her calf graze at dusk in Borana Conservancy, one of Kenya’s newest and most successful rhino sanctuaries.

Students from Sang’a Primary School visit Borana Conservancy to learn about the importance of ecological preservation.

As the sun sets over the Conservancy, a foal and its stable hand relax. Borana houses many horses available for safaris.

An Encounter with Rhinos

On my final day in Borana, Elaine and I crest a hill, and I notice her watching two grey shapes ahead. It’s a rhino calf and its mother, who slowly moves to position herself between us and her young.

Elaine stops, and we lock eyes with the rhinos. It’s fascinating—these two animals are each other’s closest living relatives. Despite their differences, they seem to find a quiet understanding. We keep our distance, and the rhinos return to grazing. I relax in the saddle, finding myself focusing less on their differences and more on their shared traits: their soulful eyes, strong jaws, and slow, deliberate movements.

Riders stop to watch elephants during a safari in the Lolldaiga Hills.

The diversity of life in the wild is a constant source of wonder, full of contrasts and unexpected connections. As the sun sinks behind the hills, I nudge Elaine. She turns away from the now calm rhinos, and we head back home.

What to Know:

- Getting There: You can fly with Safarilink or AirKenya from Nairobi’s Wilson Airport to the Lewa airstrip, where Borana guides will pick you up. Alternatively, you can take a four-hour drive from Nairobi or fly to Borana’s airstrip, just 10 minutes from the lodge.

- More Activities: Horseback riding is available for all levels, but experienced riders can enjoy a faster pace and travel farther. Additional activities include mountain biking, bush walks, bird watching, and cultural experiences, as well as vehicle safaris to explore the landscape and wildlife near Mount Kenya.

- Accommodations: The boutique lodge sits on a hillside above a dam that attracts plenty of wildlife. It offers four standalone cottages and two family cottages, each with its unique character. All rooms feature large baths, fireplaces, and outdoor verandahs. Rates include full board with meals made from fresh, local ingredients, all activities within Borana, and a 24% contribution to the conservancy’s conservation efforts. Rates range from $830 in the standard season to $1,110 in peak season, with discounts for children under 16.

- When to Visit: There’s no bad time to visit, but the months after the rains in June and July, or December and January, are particularly beautiful when everything is lush. As of January 2024, visitors no longer need a visa to travel to Kenya.